The scientific method is the traditional process of making an observation, forming a hypothesis on a predicted outcome, conducting an experiment, gathering data and measuring, and drawing a conclusion. The process could then start again by refining the original hypothesis or, if the results confirm our starting hypothesis, a theory can be formed. The eleventh century physicist Alhazen (Ibn al-Haytham) is considered the father of the scientific method.

Back when I was a master student of mechanical engineering, I did many experiments following this method. For an engineering problem, the scientific method works well, given that we know those significant properties that need to be measured to evaluate an experiment.

But those of us who work on high complexity projects that involve people know that not all of our problems can be measured this easily.

Ken Schwaber in Agile Software Development with Scrum distinguishes two types of process control: defined and empirical. A defined process is repeatable and predictable, it provides the same output given the same input. A production or an assembly line is a good example for this. Software development (a complex project) as it involves lots of uncertainty cannot be controlled with a defined process. Although, software projects still need to be controlled to prevent chaos, for those, empirical process control can be used. Scrum (the most popular software development framework) applies empirical process control principles. The three “legs” of empirical process control are transparency, inspect, and adapt, which is an adaptation of the scientific method into software development. Whether it is called empirical method, scientific method, iterative method, PDCA (Plan, Do, Check, Act) cycle, or continuous improvement, they all rely on measurements.

Why do we create metrics?

As I am a mechanical engineer converted into an Agile Coach, I love numbers, I love to measure things, and I feel comfortable when something is backed up by science and data.

Before creating a metric it is important to clarify our intentions. Do we need to have this metric to help us decide something, or do we need to have them to monitor our progress toward a goal?

Management often asks for reports and metrics to prove that employee time is usefully spent. Some things can be measured easily. For example, creating high quality software and reducing bug-fixing time are common goals of any software company. Luckily, the number of bugs per sprint or hours of work to correct bugs are easy things to track. But what happens if we like to spend our time improving not so exact things, like employee motivation, team collaboration, or what makes people happy? Creating a metric and getting a quantitative result is much harder when people and feelings are in question.

How to avoid vanity metrics

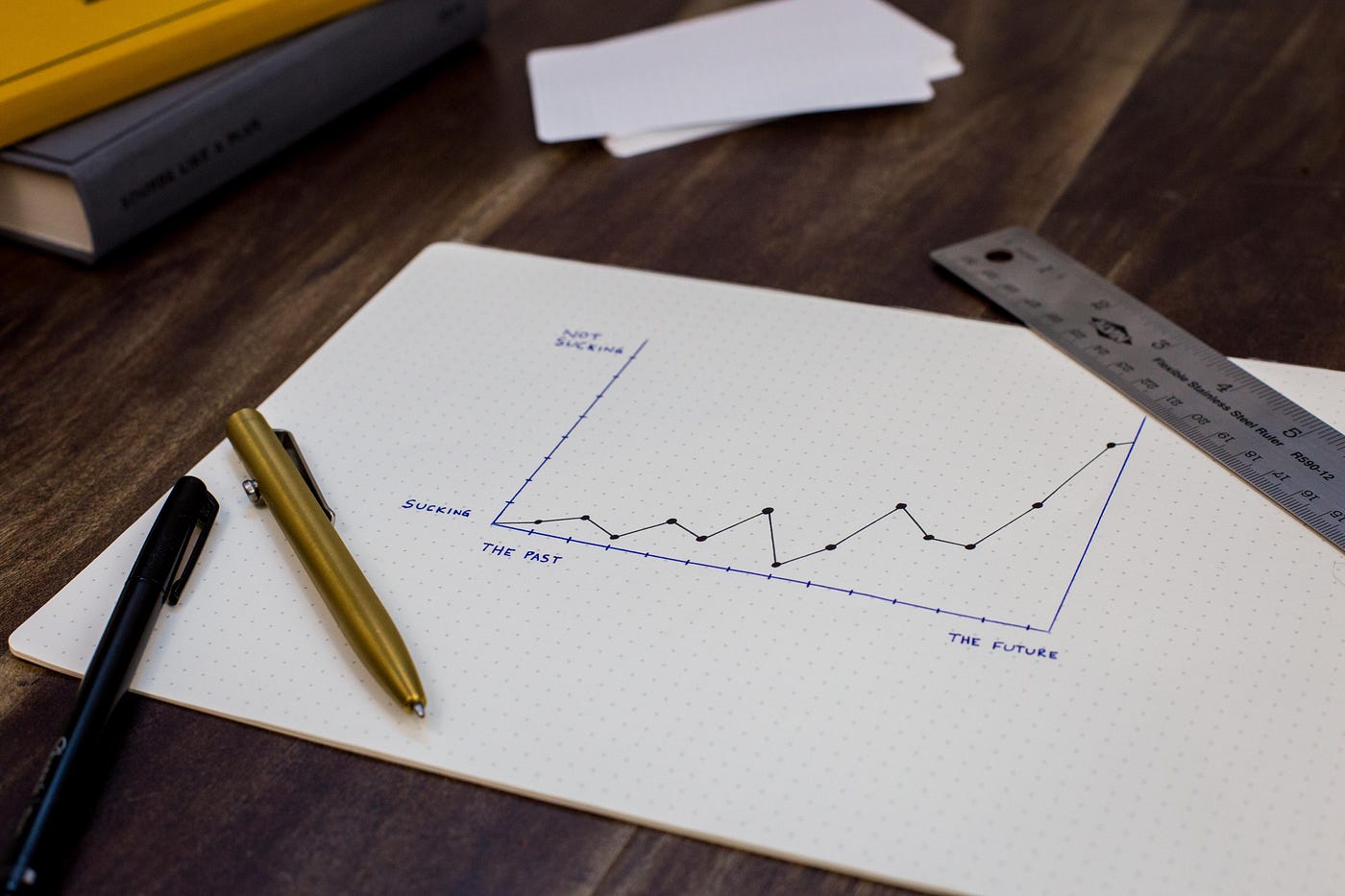

The opposite of a good metric is a vanity metric. This term was introduced by Eric Ries in The Lean Startup. Vanity metrics are those easily measurable magic numbers people brag about while having a beer with colleagues. One of my personal favorite vanity metric is the number of sales leads, which really means nothing without the lead-to-business=conversion rate.

Another example could be the number of bugs resolved or completed story points per sprint. Alone, they mean nothing. Vanity metrics do not provide a clear picture on the effects of our actions. If a vanity metric goes up everybody wants to take credit but when it declines it is always blamed on an outside action, the economy, or the weather.

How do we create metrics of value?

Jurgen Appelo addresses the topic of metrics and measurements in his new book Managing for Happiness and suggests 12 rules to be followed in the Metrics Ecosystem. The Scoreboard Index is offered as a solution to measure team performance, taking into account all sort of metrics that would mean nothing individually but together can show the direction a team or project is heading.

Should we measure everything?

I do not think so or not in a quantifiable manner. There are actions and experiments that would not bring easily quantifiable results to an organization. For example, time spent on teaching coding-skills of fortifying team identity affect motivation, which affects employee happiness, but isn’t exactly quantifiable.

In the end these not easily quantifiable things like motivation, software craftsmanship, and employee happiness also decide if a business is successful.

Replies to This Discussion